Happy TS12 Day – although I’m writing this during the late hours of October 2. I’m excited for TLOAS because it will fall into one of my favorite Taylor categories: October albums. Collectively, these albums have introduced us to Taylor,[1] dropped pop perfection singles out of nowhere,[2] and reflected her unrivaled ability to capture the devastating combo of young love and heartachey autumn nostalgia.[3] In honor of her last original work before Lucky Number Thirteen, I’m compiling and ranking my five favorite legal battles that Swift has wrought over the years. If possible, to keep this lighthearted and celebratory, I’m sticking mostly to the music because Swift has, of course, gone through litigation nobody should ever have to face.[4]

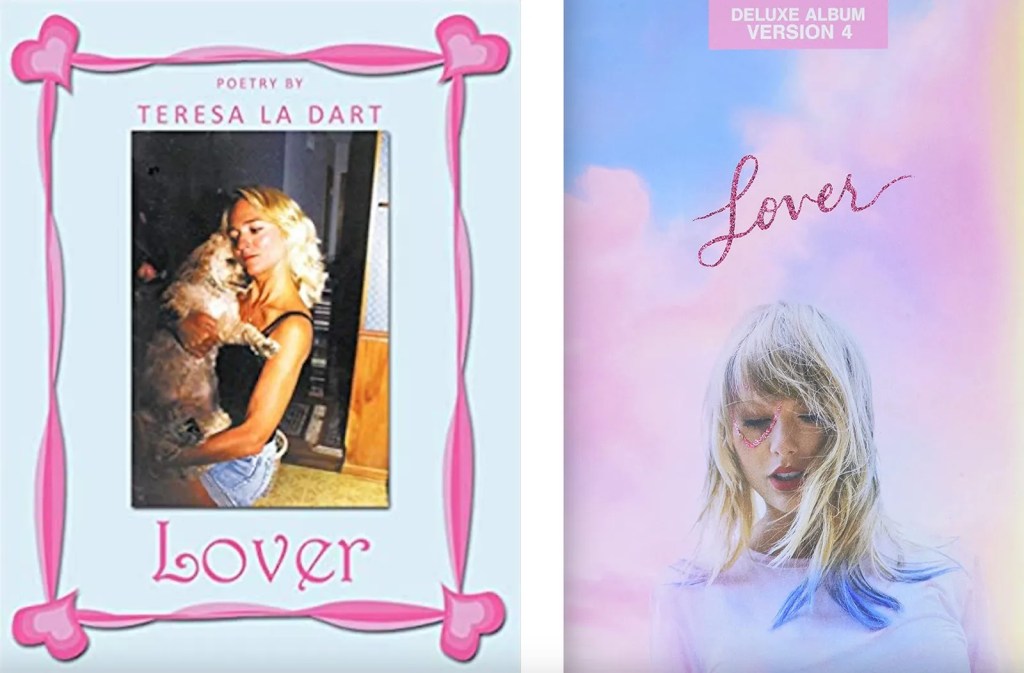

5. The Lover Cover

Poet Teresa La Dart’s claim was a copyright infringement lawsuit alleging Swift’s 2019 Lover deluxe book copied the “look and feel” of her 2010 poetry book.[5] La Dart pointed to broad similarities – namely, soft pink pastels – rather than exact copying. See a comparison of the two covers below. La Dart’s case was quickly dismissed. Not a threatening or sordid controversy, but some fans had fun rolling their eyes at the idea of one of the world’s biggest superstars scouring the internet high and low so she could rip off an independent artist’s own memoir (one Reddit user commented: “so taylor is essentially being sued for scrapbooking”[6]).

4. Shake [the lawsuit] Off

Another pretty frivolous copyright claim, the Shake It Off cases turned on whether Swift had infringed copyright-protected lyrics from the 2001 song Playas Gon’ Play. Copyright protects original expression, but not short, common phrases or stock ideas — what courts call the idea-expression dichotomy.[7] The plaintiffs argued “playas gonna play” and “haters gonna hate” were original enough; Swift’s team argued they were clichés. Courts agreed with Swift’s view, and the plaintiffs eventually dropped the suit. Thus, even Swift’s worst lyrical samples[8] aren’t immunized from legal challenges.

3. Evermore Park Trademark Dispute

When Evermore Park sued Swift, the legal claim was trademark infringement under the Lanham Act — the park argued consumers would be confused into thinking her album evermore[9] was connected to their fantasy venue.[10] Trademark law protects against consumer confusion, but the law says that you can’t monopolize a common word unless confusion is plausible.[11] Swift’s team countersued for the park’s copyright infringement because they were publicly performing her songs without a license. That part is reminiscent of “opening the door,” a concept we learned in evidence this week: sometimes when you’re getting sued, the rules don’t let the plaintiff bring up certain kinds of evidence – unless you do it first (inadvertently or not). Once you do that, your theory could get completely ruined.[11] So, don’t do something that’s gonna expose you legally, like suing Taylor Swift on a legally deficient claim.

2. Cease-and-Desist against Kanye West

After VMA-gate in 2009, West didn’t leave Swift alone. In 2016, he and then-wife Kim Kardashian spammed the internet with false claims she had approved the degrading lyrics in his misogyny-laden Famous. Defamation law protects against false statements that damage reputation; West’s rants about Swift fell squarely into that zone. Swift asserted her rights without filing suit, putting him on legal notice that his rants could easily have imposed liability under the law.[13] And West’s more recent behavior is certainly indicative of something more alarming than celebrity-on-celebrity hate, which is admittedly not among the most devastating legal wrongs. But long-time fans remember the straight-up misogyny of the “#TaylorSwiftIsOverParty” era, and I like that Swift, always able to turn her life into art, got some poetic justice here by writing an album inspired by a classic tort claim.[14]

1. The Masters (not the golf tournament)

Nearly everyone knows the lore: when Big Machine Records CEO Scott Borchetta sold Swift’s first six albums to Scooter Braun, the core legal issue was ownership of the master recordings. Under most record contracts, labels own the masters, and artists only have royalty rights. Swift’s refusal to accept this arrangement, and her decision to re-record her songs, was a brilliant legal workaround: U.S. copyright law treats each recording as its own copyrighted work.[15] By creating Taylor’s Version, she undercut the market value of Braun’s masters and regained control of her catalog. It’s just so epic because she created a new monolith in the artists’ rights world by exposing a standard label practice for what it really did to her artistic freedom. Before Swift, most fans – and the public, probably – didn’t know what “owning your masters” meant. Now it’s commonplace pop-culture vocab – and hopefully binds labels to be more equitable with artists big and small.

[1] See generally Taylor Swift (Big Mach. Records, Oct. 27, 2006) (providing such watersheds as Picture to Burn and Teardrops on my Guitar). The author apologizes for non-adherence to Bluebook Rule 18.7.1 in this post.

[2] See Midnights at Karma; see also 1989 at New Romantics, Is It Over Now? (From the Vault) (Big Mach. Records & 2023 Taylor’s Version).

[3] See Red at All Too Well (10 Minute Version) (Taylor’s Version) (From the Vault) (2021).

[4] See Mueller v. Swift, No. 15-cv-01974-WJM-KLM, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 50291 (D. Colo. Apr. 14, 2016) (claiming defamation against Swift when she alleged Mueller sexually assaulted her). The jury awarded the $1 in damages that Swift requested in her counterclaim alleging assault. See Jury Verdict, Mueller v. Swift, No. 15-cv-01974-WJM-KLM, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 50291, at *2 (D. Colo. Aug. 15, 2017) (finding for Swift).

[5] See Nina Corcoran, Taylor Swift Sued over Lover Design, Pitchfork (Aug. 24, 2022), https://perma.cc/4ETB-LYNP.

[6] u/candidlykaylor, Reddit (r/TaylorSwift), https://publish.reddit.com/embed?url=https://www.reddit.com/r/TaylorSwift/comments/wwry0s/comment/ilmwjr4/ (last visited Oct. 2, 2025).

[7] See 2 Patry on Copyright § 4:31 (2025); see also Holmes v. Hurst, 174 U.S. 82, 86 (1899) (holding that copyright law does not protect specific words which are common to everyone).

[8] But see evermore, tolerate it at 2:50-3:35. A judge called the lyrics in Shake it Off too banal for the plaintiffs’ claim to survive.

[9] The author’s personal favorite.

[10] See Chris Willman, Taylor Swift and Evermore Park Drop Lawsuits Against One Another, with No Money Exchanged, Variety (Mar. 24, 2021), https://perma.cc/S8EB-JQG5.

[11] See Fed. R. Evid. 404(a)(2); 407.

[12] Some critics argue that Swift is too trigger-happy with cease-and-desist letters in general, unfairly sweeping up innocent and small-time actors. But here’s a case where she was for sure acting reasonably.

[13] Some critics argue that Swift is too trigger-happy with cease-and-desist letters in general, unfairly sweeping up innocent and small-time actors. But here’s a case where she was for sure acting reasonably.

[14] See reputation (Big Mach. Records 2017).

[15] See 17 U.S.C. § 102(a)(7) (defining audio recordings as separately copyrightable works).

Leave a comment